Ideas

Blog

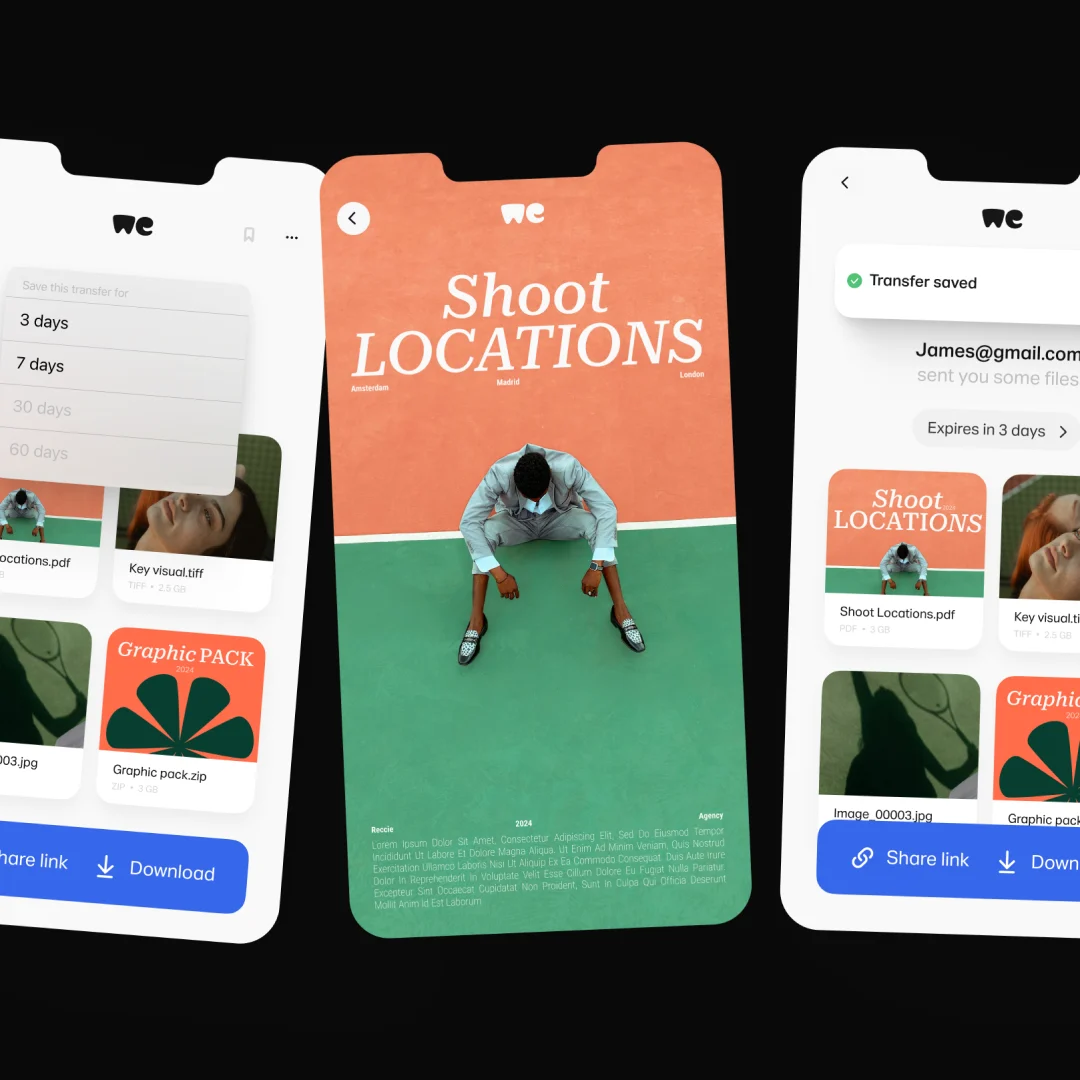

2025 WeTransfer plans remix—see our latest plans

Save for now. Get to it later

Unleashing our next era of growth, with Bending Spoons

Explore all

“Move it like a Pro” campaign highlights simple tools that help creators

“Move it like a Pro” campaign highlights simple tools that help creatorsA behind the scenes look into WeTransfer's latest brand campaign

New Rules: Inspiring creatives at a difficult time

New Rules: Inspiring creatives at a difficult timeWe’ve launched a guide to help photographers navigate an industry in flux

Creating a world? Join our new research project

Creating a world? Join our new research projectSubmit your projects to get published in our new memo, take part in our research and get paid for doing it.

Talk to the Moon: one giant leap for WeTransfer

Talk to the Moon: one giant leap for WeTransferThe story of Talk to the Moon: a wonderfully strange AI experience, brought to life on WeTransfer

Why we’re giving everyone at WeTransfer Fridays off over the summer

Why we’re giving everyone at WeTransfer Fridays off over the summerIntroducing WeTransfer Time Off: summer edition, with every full Friday during July and August granted as a day off, without changing our work patterns Monday to Thursday or adjusting compensation and benefits

Season 4 roundup - Influence Podcast

Season 4 roundup - Influence PodcastDuring this season we talk to UK-based fashion designer Harris Reed and Oscar-winning actor, writer, producer and musician Riz Ahmed, plus more

Season 3 roundup - Influence Podcast

Season 3 roundup - Influence PodcastThroughout this season Damian chats to Ben & Jerry's co-founder Jerry Greenfield and explores what happened behind closed doors at Cambridge Analytica, plus much more

Season 2 roundup - Influence Podcast

Season 2 roundup - Influence PodcastDuring this season we explore the complexity of being black in America, non verbal communication, plus more

Season 1 roundup - Influence Podcast

Season 1 roundup - Influence Podcastinfluence-podcast-by-wetransfer-season-1

We’re launching our next act

We’re launching our next actSupporting the next generation of creatives

Meet Holley M. Kholi-Murchison, Our New Creative Researcher-in-Residence

Meet Holley M. Kholi-Murchison, Our New Creative Researcher-in-ResidenceThe social practice artist sheds light on how our first creative residency came to life

Alva Skog has an idea

Alva Skog has an ideaYou might notice some cheeky new artwork during your transfers by this Swedish artist. Here's how they came to life.

Designing the 2020 Ideas Report

Designing the 2020 Ideas ReportTo show the impact of a year of chaos on the creative mind, we had to think outside the box

When the going gets tough, the tough get going

When the going gets tough, the tough get goingCovid-19 has offered an unexpected opportunity for creatives to reset and innovate

From Idea to Idea App in 3 Days Flat

From Idea to Idea App in 3 Days FlatHacking together an idea at the WeTransfer Hackathon

Apple's SwiftUI

Apple's SwiftUIHow Collect experienced integrating this new technology

Giving back to the open-source community

Giving back to the open-source communityHow the engineers at WeTransfer came together to support the open-source community

More voices = better ideas

More voices = better ideasOur mission to bring more diverse voices to the table (and make sure they’re heard)

Nelly Ben Hayoun and Arjun Appadurai on counter culture & education

Nelly Ben Hayoun and Arjun Appadurai on counter culture & educationSupporting pluralistic thinking with the University of the Underground

The Trust Manifesto by Damian Bradfield

The Trust Manifesto by Damian BradfieldIf you could reinvent the internet now, what would it look like?