If Kickstarter is a vibrant hub of creative ideas people really believe in, then Flopstarter is its evil twin. The brainchild of British artist Oli Frost, Flopstarter is billed as “a platform for bad ideas.” These include a chat app that forwards every message you send on to your partner, “reverse Viagra” which induces hallucinations of your parents having sex to stifle your own horniness, and “a bowl that’s almost flat, like a plate, but it’s a bowl.”

Flopstarter is my favourite sort of project; super-silly on the surface but actually quite thought-provoking. What makes a bad idea? What is the relationship between bad and good ideas? And what role do bad ideas play in the creative process?

These questions are at the center of the second annual WeTransfer Ideas Report. Last year we asked 10,000 creatives how, where and when they get good ideas. This year we decided to focus on how ideas develop. How many ideas do we need? How do we work out whether an idea is any good? And what do we consider when we think about an idea’s potential?

The headline finding from the 20,000 people who completed this year’s survey is that you need more ideas than you think. Lots more. Most people (72%) end up using half of their ideas or fewer. Nearly one in five people said they use less than 10% of the ideas they have – a beautifully terrible hit-rate.

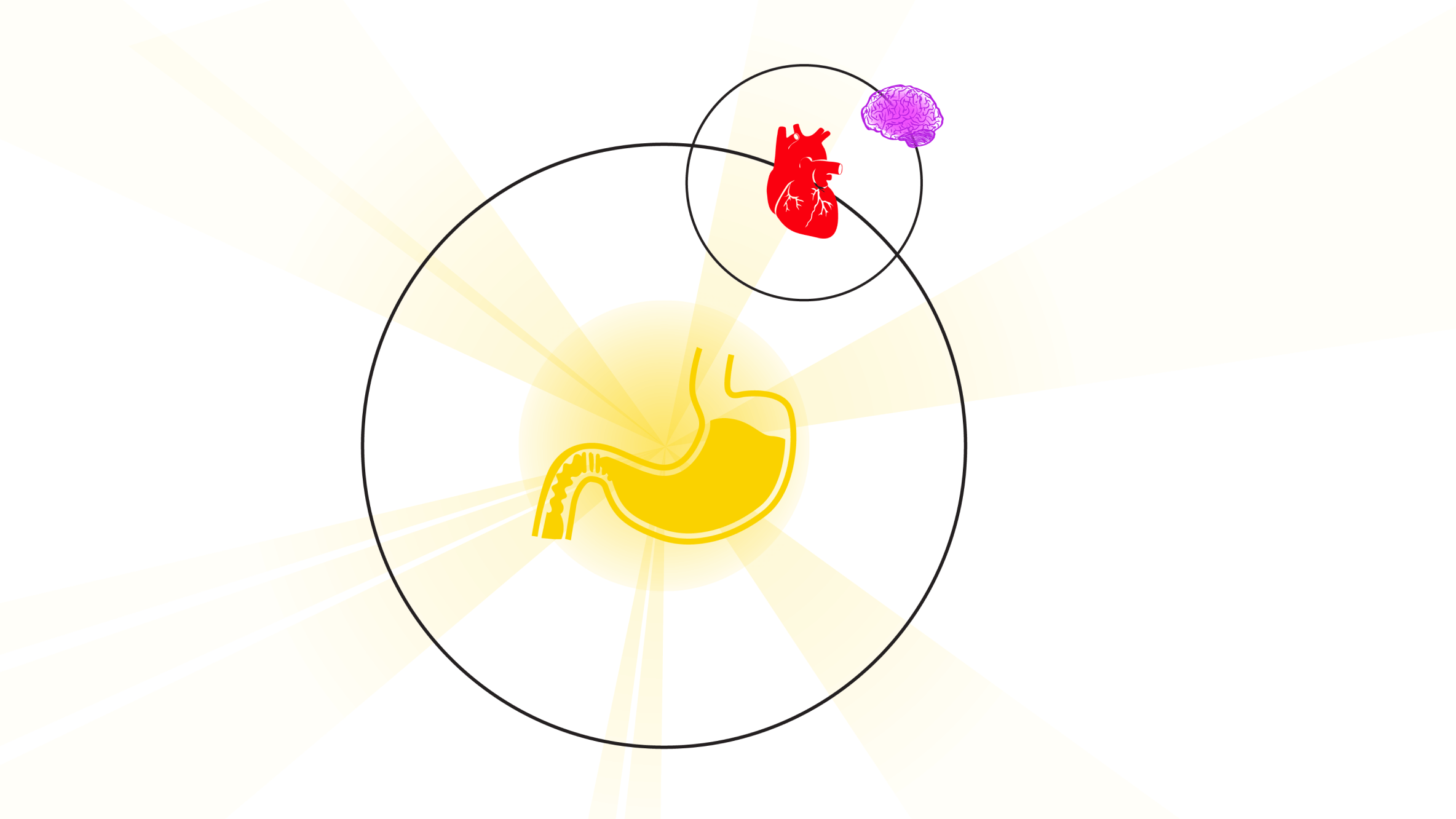

It’s helpful to think of creativity as a two-step process. The first step is idea generation, which we looked at in last year’s report. The second step is to evaluate the pool of ideas you have and select the ones you want to work on.

Now for the science part. Back in 2009, researchers from INSEAD and the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School wrote a study called Idea Generation and the Quality of the Best Ideas. They divided students into different groups and challenged them to come up with ideas for new products which were then scored on a quality scale for how innovative they were.

Their findings were pretty definitive. The group that had more ideas had better ideas. This makes sense – the bigger the pool you have to choose from, the more intense the competition and the higher the standard of ideas that get through to the next stage. As the authors of the report put it, the five tallest people in a city of one million people will be taller than the five tallest people in a city of 10,000 people.

But the researchers also noted the importance of variance, which is the range of ideas across the quality spectrum. As they write, “the extremes are what matter, not the average or the norm… In most innovation settings, an organization would prefer 20 bad ideas and one outstanding idea to 21 merely good ideas.”

Which brings us back to Oli Frost, reverse Viagra and flat bowls. Flopstarter is funny because it sets up its products as the inverse of the good ideas that people are trying to get off the ground on Kickstarter.

But seeing it as a single continuum, with bad ideas at one end and genius ideas at the other is wrong. It’s time to stop thinking in binary terms of good and bad ideas. All ideas help frame and contextualise each other, like pool balls on a table mid-game. When you step up to assess your options, some shots are simpler than others. Some are risky, some are predictable, some seem impossible but open up at a later stage.

We believe it’s time to rehabilitate bad ideas as a fundamental part of the creative process. In fact – when we take variance into account – the worse the better, if they create space where you might have one or two golden ideas as well.

As part of the INSEAD/University of Pennsylvania research, the students were divided into one group that worked as a team, coming up with ideas together, and another group that worked in a so-called hybrid way, where students went away and worked on their own ideas before bringing them back to the group.

Again the results were pretty clear: the hybrid group generated three times as many ideas as the team group. The hybrid group was slightly better at evaluating the quality of ideas, although neither group was brilliant at this. The researchers also found no evidence that what we think of as brainstorming – building on each other’s ideas in a group – was an efficient or effective way of reaching good ideas.

This echoes one of the most surprising results from our survey. In the creative world we hear an awful lot about collaboration, but it seems that while working together is essential to bring an idea to life, it’s not that good for shaping ideas in the first place. 78% of creatives said they decide on their own whether an idea is any good or not (47% will do some of their own research, 31% just trust their gut). Only 18% said they ask family, friends or colleagues to help them decide if an idea if worth following up.

This has huge implications for companies or other organizations which need to promote creative thinking. For the second year in a row, when we asked what gets in the way of having ideas, “my job” was the highest answer. Given that between 75 and 90% of our respondents seem to be full-time working creatives, that’s a lot of people who aren’t able to focus on having and developing their ideas.

Our survey and the scientific evidence suggests that brainstorm sessions and other creative meetings may well be a waste of time. Send people off with the time and space to think properly and the quality of their ideas will probably improve.

For the first time this year, we tried to dig into the process of evaluating ideas. What do we ask ourselves when trying to weigh up whether we should commit to an idea or not? This question threw up our favourite single finding of the report.

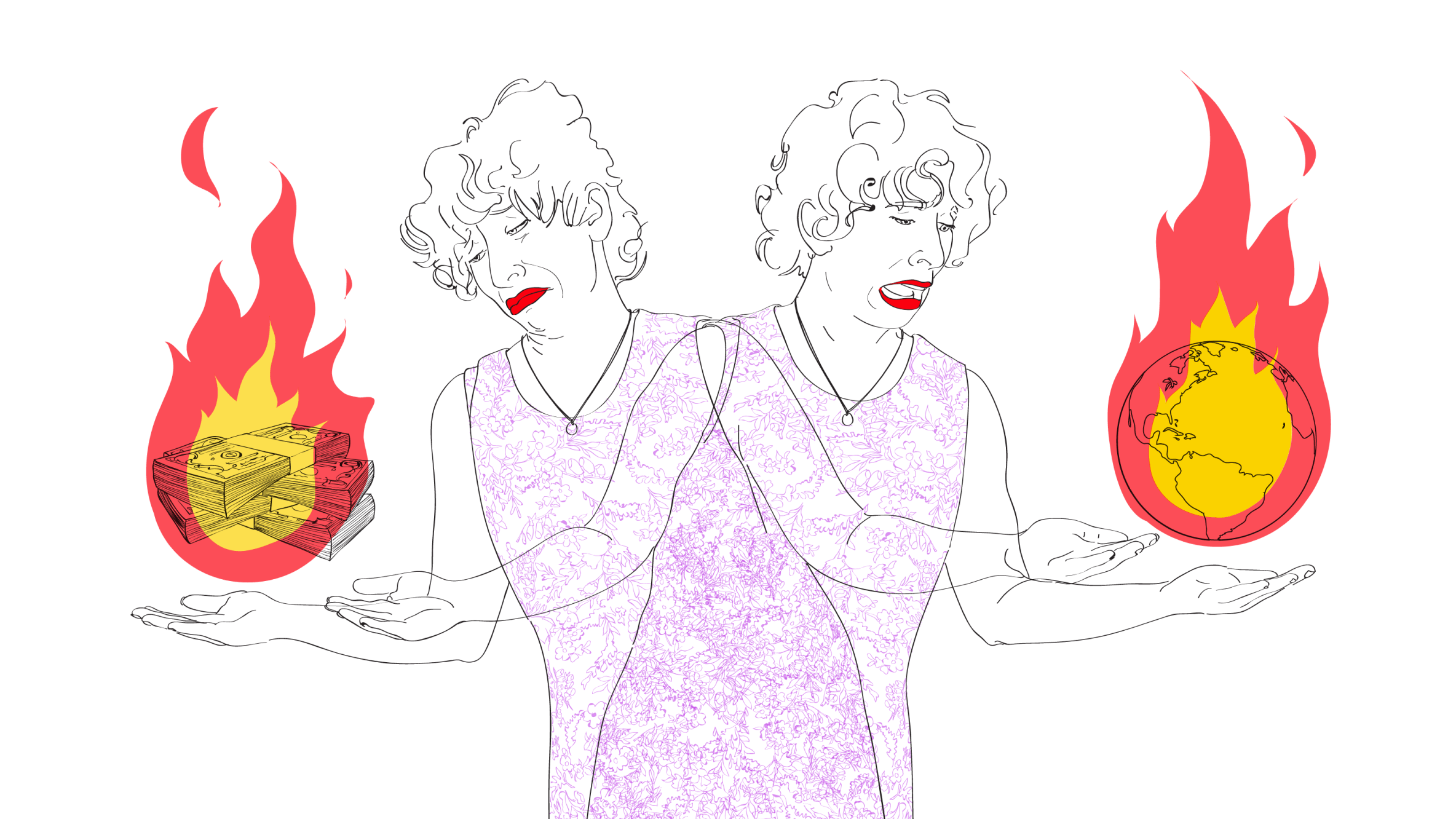

There wasn't much in it, but “Will it make the world better?” at 27% pipped “Will I make money with it?” at 26%. As the world burns, both literally and metaphorically, it’s hugely hopeful to hear that creative thinkers feel responsible for coming up with ideas to try and save it. Not all creative ideas change the world, but every idea that truly changes the world is creative.

Read the full report here.